Risk at the Margin

2021-04-02

Humans are, generally, pretty awesome at risk management. Why, then, do we seem to be so bad at it – and in so many different ways – when it comes to assessing risk in the CoViD era?

Risk Models

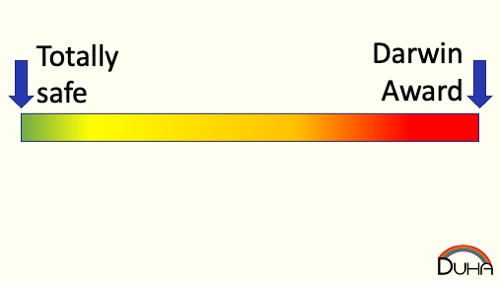

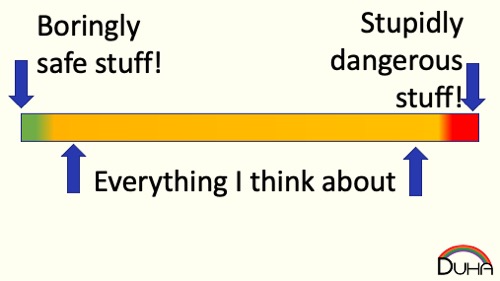

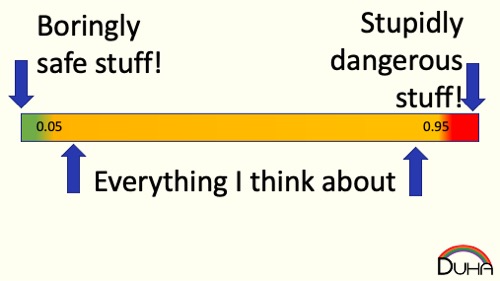

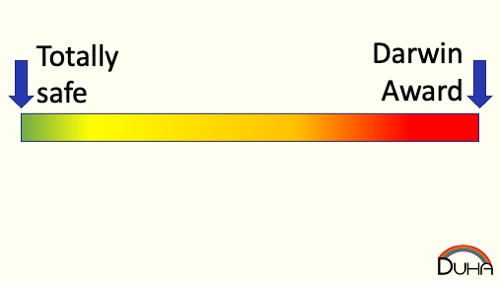

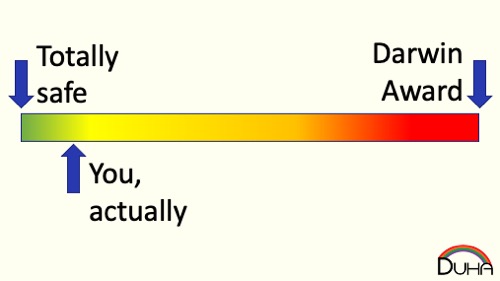

First, let’s talk about how humans make most risk decisions. Risk comes in a lot of different flavors (injury, long-term health, short-term health, embarrassment, financial, ….), and everyone weights those flavors differently. For simplicity, I’m going to talk about risk as if it lives on a single, linear scale, like so:

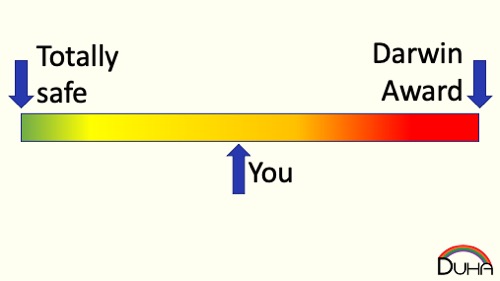

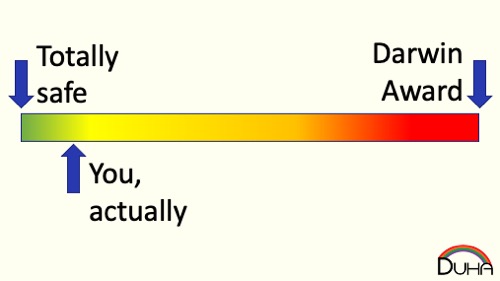

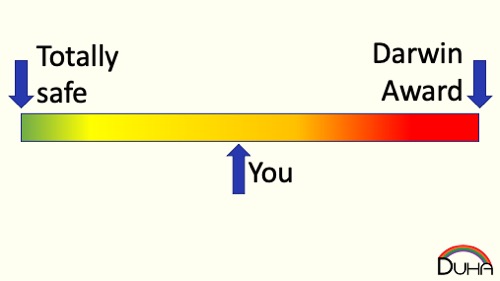

A human has an aggregate risk tolerance, somewhere on that scale:

Really, you’re almost certainly all the way over on the left. Humans are really risk averse, because we think we’re sort of immortal, and we don’t want to jeopardize that.

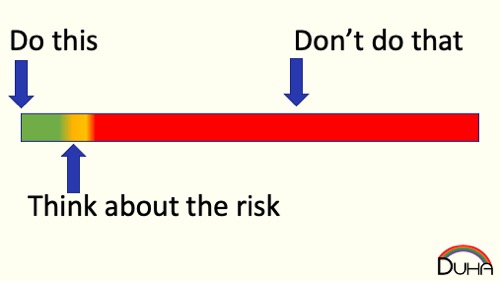

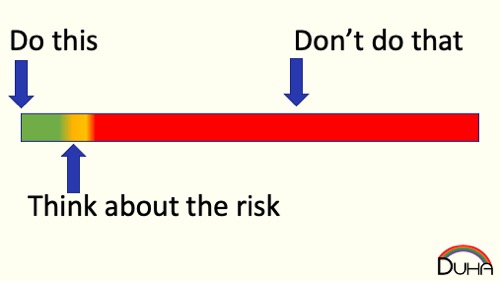

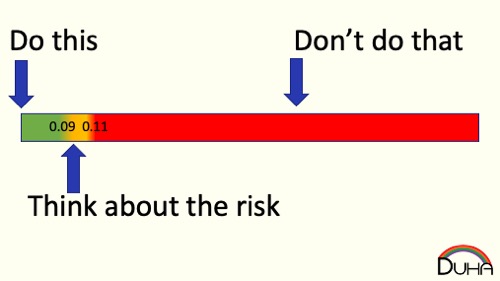

When you assess an activity, you’re quickly going to put it either to your left (Safe! Do this!) or your right (Unsafe! Don't do that!). While the “safe” activity might actually increase your risk, it seems like an activity you already accept, so you probably don’t consider it to, on the whole, make you less safe. For only a tiny amount of decisions do you need to actually think about the risk.

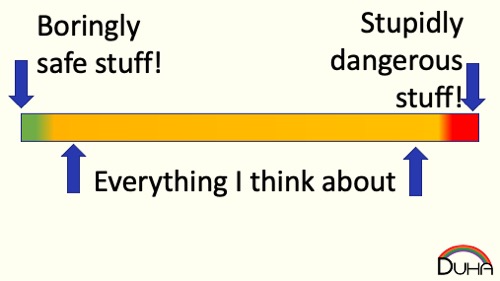

That area in between “safe” and “unsafe” is really small. Most of the time, you don’t ever have to evaluate a set of choices that sit on the margin between safe and unsafe, or be forced to pick between two unsafe activities. The distance between safe and unsafe is extremely small, although from our personal perspective, it seems massively large, since just about all risk decisions that we ever think about happen inside the margin.

This presents a hazard for us: we believe that the decision between "safe" and "unsafe" is really obvious, because the choices are so far apart, when, really, many of these choices are separated by a tiny amount, and even small errors in our decision-making process may put something on the "wrong" side.

Making decisions

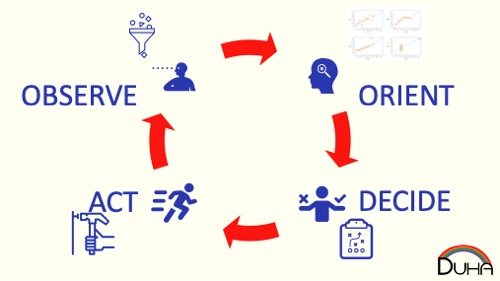

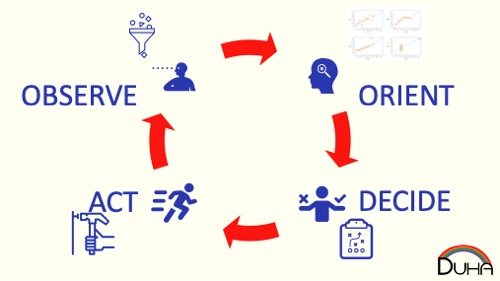

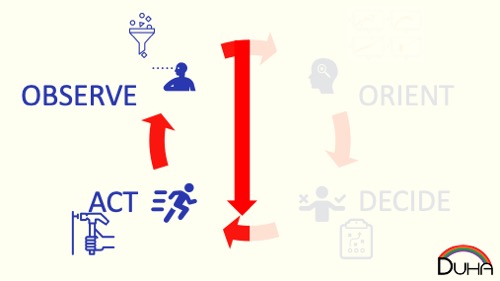

Human decision-making can be modeled using Boyd's OODA Loop: we observe an input, we orient that input to our model of the world, we decide what we should do, and then we act on our plan.

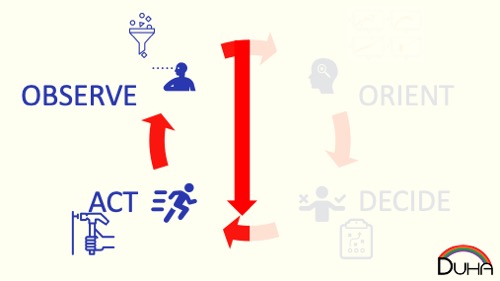

We do this so often, that our brains have optimized to perform our decision-making without thinking about it. We're like a machine-learning algorithm on steroids; our minds rapidly pattern match to get to a quick, cognitively-cheap, good enough solution, so you move from "Observe" to "Act" before you can even get introspective about your decision.

Orientation often starts with pulling models you think you know about, and using those as rough approximations. So CoViD might be “like the flu, but worse,” even though CoViD risk bears less resemblance to flu risk than cricket has to baseball. Sure, we can plan going to a cricket game by starting with the baseball rules and modifying them until we have cricket, but your sense of a three-hour game is woefully inaccurate.

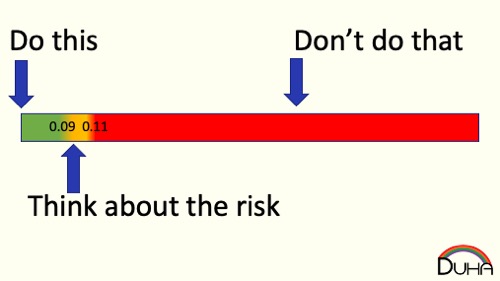

One failure mode is that once you bucket a novel risk on one side of your margin or the other, you will not consider it further. “CoViD is just like the flu, so I’ll behave normally” and “CoViD is the end of the world, let’s enter a post-apocalyptic dystopia” might describe ways this failure mode might kick in. Once you've bucketed the risk, it becomes really hard to move from "unsafe" to "safe." Let's put some arbitrary numbers onto our risk scale. Perhaps the most risk you'll accept to keep something in the "safe" bucket is 0.09 risk units, and the lowest risk that puts something in the unsafe bucket is 0.11 risk units.

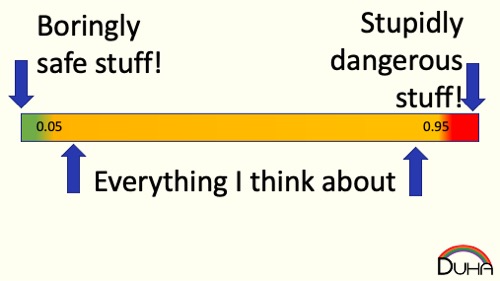

So it should seem like subtracting 0.02 risk units should let us change our decision. Unfortunately, we're really reluctant to change our minds about risk, and that partly because, once we think abut risk, we feel like we take a lot of risk - and our margins are much larger to us, perhaps ranging from 0.05 risk units all the way up to 0.95.

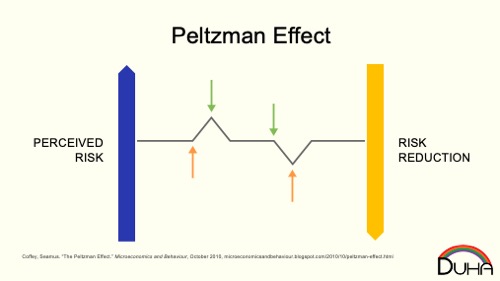

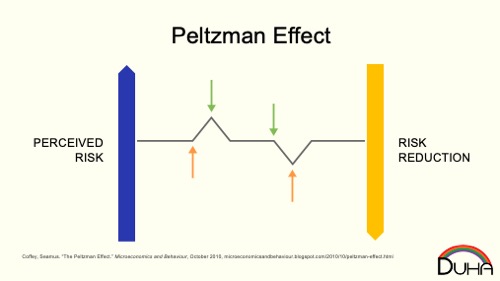

A different failure mode starts when you might correctly identify that the aggregate risk is in the margin, and requires complex thought (“I can stay home to avoid CoViD, but then I won’t make any money and I might go stir-crazy, so how do I safely engage”). You might miss steps that would be helpful: KN95 masks, fresh air, allow air diffusion before sharing a space, don’t sing in an enclosed area. You’ll need to mitigate: as your perception of risk goes up, you’ll take safety measures to push it down. (Note that as your perception of risk goes down, you’ll remove safety measures to let it come back up).

Using the flawed model of CoViD-as-flu-but-worse, you might convince yourself that certain mitigating steps will help more than they do: rigorous surface washing, eliminate shared objects, wear lightweight cloth masks everywhere. You think you've reduced the risk of your choices down into the safe zone, even if you haven't. (Or your risk was in your safe zone, but you were wrong about the risk, and the safety theater measures you engage in aren't changing your risk). On the other hand, you might use the inverse (and also flawed) model of CoViD-as-flu-but-better, and convince yourself that it's okay to take even more risks, because the people telling you it's dangerous are clearly wrong, so what else are they wrong about?

The Failure of Expertise

It's natural to want to ask for help. You ask an expert, “is this safe?” That’s a loaded question. Almost nothing is “safe”. While you really want to ask, “Given that I’m comfortable with this level of risk, what actions should I be taking?,” a risk expert hears “Tell me everything is okay,” and they aren’t going to do that.

Only you can make risk choices on your behalf, because only you can decide if the reward is worth the risk for you. An expert, who isn’t you, is generally going to err on the side of extreme caution, because they have an entirely different risk problem: If they say something is “safe,” and there is a bad outcome, it’s their fault and they get blamed. And since they’re often dealing across a population, even most “sort of safe” risks still pose a risk to someone in the population, so it’s easiest to have a very rigid canonical answer: Don’t do anything.

Experts in an area risk functionally end up only being able to veto things, because it’s too dangerous to do anything else. There is no incentive for an expert to ever suggest removing a safety control, even it is is high-cost and useless, because for them, the downside is too massive.

Confirmation Biases

If you make a “wrong” decision, it’s really hard to correct it, without radically new data. If you put a group of activities on the wrong side of your risk tolerance, revisiting it generally requires you to be able to challenge every risk choice you’ve ever made. That’s … not easy. Even somewhat new data is easier to discard if it challenges your decisions, or easy to rigorously hold onto if it supports them (even if it later turns out to be incorrect).

Inspecting your models is one of the most helpful things you can do, but it’s hard; especially if you’ve been arguing loudly against people who made different choices than you. You risk the embarrassment of agreeing with someone that you’ve said was foolish, so it’s simpler to dig in.

Risk at the Margin

That risk that lives in your margin you might have adjusted to push it just barely to one side or another (“I’ve mitigated risk enough that I choose to do this” vs. “I can’t mitigate this risk so I won’t do this activity”). However, you are likely now going to stop inspecting that risk; it’s either in the Safe or Unsafe buckets. Most people don’t waste cognitive capacity keeping track of marginal risk once they’ve bucketed it.

Boiling the Frog

If it’s hard to deal with a wrong risk choice, consider how much harder it is to deal with a mostly right risk choice, when the world changes and now that choice becomes wrong. As incremental evidence comes in, you’re going to keep your choice on whichever side of your risk tolerance you placed it, because that’s easier. But if you’d just barely moved it to one side, ignoring evidence that it is pushing to the other side is dangerous … but really easy.

Make your Predictions

One way to treat this risk confusion is to commit to predictions in advance. “When all the adults in my house are fully vaccinated, then they can go eat lunch at a restaurant.” That’s a safe commitment to make in advance, but harder to do in real time; but by depersonalizing a decision a little bit – you’re making the decision for your future self, so you’re a little more invested than an expert – you can engage conscious risk decision-making to your benefit.

Risk Models

First, let’s talk about how humans make most risk decisions. Risk comes in a lot of different flavors (injury, long-term health, short-term health, embarrassment, financial, ….), and everyone weights those flavors differently. For simplicity, I’m going to talk about risk as if it lives on a single, linear scale, like so:

A human has an aggregate risk tolerance, somewhere on that scale:

Really, you’re almost certainly all the way over on the left. Humans are really risk averse, because we think we’re sort of immortal, and we don’t want to jeopardize that.

When you assess an activity, you’re quickly going to put it either to your left (Safe! Do this!) or your right (Unsafe! Don't do that!). While the “safe” activity might actually increase your risk, it seems like an activity you already accept, so you probably don’t consider it to, on the whole, make you less safe. For only a tiny amount of decisions do you need to actually think about the risk.

That area in between “safe” and “unsafe” is really small. Most of the time, you don’t ever have to evaluate a set of choices that sit on the margin between safe and unsafe, or be forced to pick between two unsafe activities. The distance between safe and unsafe is extremely small, although from our personal perspective, it seems massively large, since just about all risk decisions that we ever think about happen inside the margin.

This presents a hazard for us: we believe that the decision between "safe" and "unsafe" is really obvious, because the choices are so far apart, when, really, many of these choices are separated by a tiny amount, and even small errors in our decision-making process may put something on the "wrong" side.

Making decisions

Human decision-making can be modeled using Boyd's OODA Loop: we observe an input, we orient that input to our model of the world, we decide what we should do, and then we act on our plan.

We do this so often, that our brains have optimized to perform our decision-making without thinking about it. We're like a machine-learning algorithm on steroids; our minds rapidly pattern match to get to a quick, cognitively-cheap, good enough solution, so you move from "Observe" to "Act" before you can even get introspective about your decision.

Orientation often starts with pulling models you think you know about, and using those as rough approximations. So CoViD might be “like the flu, but worse,” even though CoViD risk bears less resemblance to flu risk than cricket has to baseball. Sure, we can plan going to a cricket game by starting with the baseball rules and modifying them until we have cricket, but your sense of a three-hour game is woefully inaccurate.

One failure mode is that once you bucket a novel risk on one side of your margin or the other, you will not consider it further. “CoViD is just like the flu, so I’ll behave normally” and “CoViD is the end of the world, let’s enter a post-apocalyptic dystopia” might describe ways this failure mode might kick in. Once you've bucketed the risk, it becomes really hard to move from "unsafe" to "safe." Let's put some arbitrary numbers onto our risk scale. Perhaps the most risk you'll accept to keep something in the "safe" bucket is 0.09 risk units, and the lowest risk that puts something in the unsafe bucket is 0.11 risk units.

So it should seem like subtracting 0.02 risk units should let us change our decision. Unfortunately, we're really reluctant to change our minds about risk, and that partly because, once we think abut risk, we feel like we take a lot of risk - and our margins are much larger to us, perhaps ranging from 0.05 risk units all the way up to 0.95.

A different failure mode starts when you might correctly identify that the aggregate risk is in the margin, and requires complex thought (“I can stay home to avoid CoViD, but then I won’t make any money and I might go stir-crazy, so how do I safely engage”). You might miss steps that would be helpful: KN95 masks, fresh air, allow air diffusion before sharing a space, don’t sing in an enclosed area. You’ll need to mitigate: as your perception of risk goes up, you’ll take safety measures to push it down. (Note that as your perception of risk goes down, you’ll remove safety measures to let it come back up).

Using the flawed model of CoViD-as-flu-but-worse, you might convince yourself that certain mitigating steps will help more than they do: rigorous surface washing, eliminate shared objects, wear lightweight cloth masks everywhere. You think you've reduced the risk of your choices down into the safe zone, even if you haven't. (Or your risk was in your safe zone, but you were wrong about the risk, and the safety theater measures you engage in aren't changing your risk). On the other hand, you might use the inverse (and also flawed) model of CoViD-as-flu-but-better, and convince yourself that it's okay to take even more risks, because the people telling you it's dangerous are clearly wrong, so what else are they wrong about?

The Failure of Expertise

It's natural to want to ask for help. You ask an expert, “is this safe?” That’s a loaded question. Almost nothing is “safe”. While you really want to ask, “Given that I’m comfortable with this level of risk, what actions should I be taking?,” a risk expert hears “Tell me everything is okay,” and they aren’t going to do that.

Only you can make risk choices on your behalf, because only you can decide if the reward is worth the risk for you. An expert, who isn’t you, is generally going to err on the side of extreme caution, because they have an entirely different risk problem: If they say something is “safe,” and there is a bad outcome, it’s their fault and they get blamed. And since they’re often dealing across a population, even most “sort of safe” risks still pose a risk to someone in the population, so it’s easiest to have a very rigid canonical answer: Don’t do anything.

Experts in an area risk functionally end up only being able to veto things, because it’s too dangerous to do anything else. There is no incentive for an expert to ever suggest removing a safety control, even it is is high-cost and useless, because for them, the downside is too massive.

Confirmation Biases

If you make a “wrong” decision, it’s really hard to correct it, without radically new data. If you put a group of activities on the wrong side of your risk tolerance, revisiting it generally requires you to be able to challenge every risk choice you’ve ever made. That’s … not easy. Even somewhat new data is easier to discard if it challenges your decisions, or easy to rigorously hold onto if it supports them (even if it later turns out to be incorrect).

Inspecting your models is one of the most helpful things you can do, but it’s hard; especially if you’ve been arguing loudly against people who made different choices than you. You risk the embarrassment of agreeing with someone that you’ve said was foolish, so it’s simpler to dig in.

Risk at the Margin

That risk that lives in your margin you might have adjusted to push it just barely to one side or another (“I’ve mitigated risk enough that I choose to do this” vs. “I can’t mitigate this risk so I won’t do this activity”). However, you are likely now going to stop inspecting that risk; it’s either in the Safe or Unsafe buckets. Most people don’t waste cognitive capacity keeping track of marginal risk once they’ve bucketed it.

Boiling the Frog

If it’s hard to deal with a wrong risk choice, consider how much harder it is to deal with a mostly right risk choice, when the world changes and now that choice becomes wrong. As incremental evidence comes in, you’re going to keep your choice on whichever side of your risk tolerance you placed it, because that’s easier. But if you’d just barely moved it to one side, ignoring evidence that it is pushing to the other side is dangerous … but really easy.

Make your Predictions

One way to treat this risk confusion is to commit to predictions in advance. “When all the adults in my house are fully vaccinated, then they can go eat lunch at a restaurant.” That’s a safe commitment to make in advance, but harder to do in real time; but by depersonalizing a decision a little bit – you’re making the decision for your future self, so you’re a little more invested than an expert – you can engage conscious risk decision-making to your benefit.